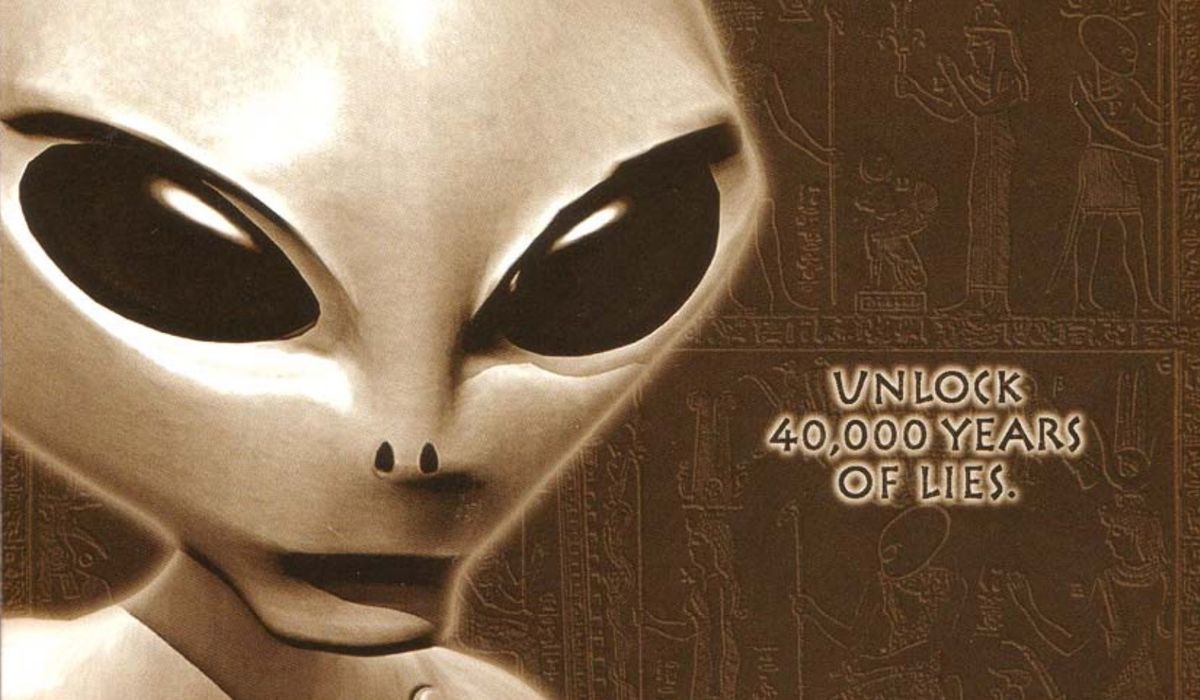

We often hear about things being ahead of their time, but ’90s cult point-and-click adventure Drowned God: Conspiracy of the Ages is unexpectedly prescient in the neurotic world of 2021. “I would have loved to publish Drowned God now,” says Algy Williams, who produced the 1996 Inscape game that tapped into planetwide conspiracies and longstanding cultural myths. “You’d have a social media department as big as the art department and developers combined, wouldn’t you?”

When Drowned God was first released, Williams recalls it rocketing into the top 10 videogame sales in the US. Now it’s largely been forgotten, though it’s probably one of the most fascinating and aesthetically experimental point-and-click games of all time.

The originator of Drowned God was writer and political cartoonist Harry Horse, who died under infamously tragic (and contested) circumstances in January 2007. In 1983, Horse forged a mysterious diary supposedly written by Richard Horne, a real 19th century poet with whom he shared a name; Horse had been born Richard Horne, but embraced “Horse” after someone misread his name at school and eventually adopted “Harry Horse” as a working pseudonym. The diary, which went into the poet’s speculations and prophecies about the world, passed for real until Horse was revealed as its author. For most this would have spelled the natural end of an artistic prank. But over a decade later, with the rise of point-and-click puzzlers like Myst, Horse decided it was time to resurrect his project as a game.

Horse approached animator and illustrator Alastair Graham, who recalls the writer contacting him “out of the blue” and coming to his house where they struck up a “pretty instant understanding.” Graham became the game’s co-creator and art director, roped in Williams, and the rest, as they say, is history.

In terms of plot, Drowned God took a somewhat “less is more” approach to hand-holding but ends up becoming a real exercise in conceptual maximalism. Drawing inspiration from the Kabbalah and tarot cards, the premise is that all of human history—everything from the Illuminati to the Roswell aliens—is based on lies and secrets, and that humanity was actually created by ancient aliens. You know, small stuff.

The player starts off in a mysterious room with the strange Bequest Globe—a gift of unknown provenance—before meeting two emissaries, Kether and Malchut, who represent different philosophies and outcomes. They must then traverse time and space to solve puzzles (designed by St Catherine’s College, Oxford enigmatist Chris Maslanka) and gather important artifacts that reveal hidden truths about all of existence.

The sheer scope of neuroses at play in Drowned God is incredible. The Obscuritory’s Phil Salvador rather astutely describes it as something that “tricks you into believing conspiracy, placing paranoia above reason, and celebrating the discovery of a grand unifying knowledge that exists because it has to.”

Salvador distills the essence of Drowned God down to a very simple idea: that to buy into the game’s deceit, and to play the game as it is meant to be played, you simply have to embrace conspiracy.

“We were trying to really push the boundaries as much as we possibly could,” Williams recalls of story, which was written by Horse. “What I thought was interesting now is that a number of things that were predicted have pretty much come true. And I think what we were talking about there, pulling together all of these conspiracy theories, it’s very, very relevant. You’ve got QAnon making the rounds now, and there weren’t that many avenues for conspiracy theories, or not nearly as many avenues for conspiracy theories to spread and grow back then.”

The mind of Harry Horse

When I ask Algy Williams and Alastair Graham about the making of Drowned God, it’s clear that both men have a carnival of memories—good and bad—associated with it. Development included a whirlwind European tour thanks to a couple of Time-Warner staffers who were having a “passionate love affair” at work. “They dragged us to a lot of interesting tourist sites in France and Europe, just because they wanted to go there,” Williams recalls with a wry smile. “So we went to Chartres, we went to Stonehenge, we went to all of it, and it was a big jolly for them.”

The eclectic team included post-punk musician Mark Burgess from The Chameleons, musical duo Miasma, two young developers named Anthony McGaw and Inigo Orduna, and animator/sculptor Greg Boulton, who worked on Peter Gabriel’s iconic Sledgehammer video. According to Williams, Horse had also been in touch with writer William S. Burroughs, whose voice “appears somewhere in the game,” but no formal voice work was commissioned and Burroughs died in 1997, making it difficult to confirm.

Shenanigans aside, a good deal of those memories involve working with Harry Horse. “Without a doubt he was one of the most talented people I’ve worked with in my 40-year career,” Williams says. “But… Harry had some very, very intense highs and very intense lows, and combining that with being a perfectionist and having a very, very clear vision of what he [wanted] to do, it was sometimes very difficult.”

Graham, who Horse directly approached to work on the game, is a little more reticent in his recollections. “The work that Harry was doing on Drowned God was a definition of him in very intense, very detailed—remorseless, one might even say—[way], and that’s what he was like,” he says. “He was very difficult to work with when he was down… but I can’t knock him in terms of vision, in terms of manual ability… he was formidable.”

Memories of Horse are clouded over by the nature of his death, said to be a suicide pact with his wife Mandy, who suffered from debilitating multiple sclerosis. In a 2008 newspaper article, her father alleged it had been murder rather than a Romeo-and-Juliet-style scenario. It’s hard to separate the paper-thin boundaries between Horse’s creative work and personal life, especially when there’s so much speculation involved in both. It’s also difficult to examine the game in retrospect without Horse’s death looming in the back of one’s mind.

Drowned God remains one of the most distinctive parts of Horse’s legacy. It’s a forgotten relic of early motion capture games and a bold statement for the power of experimental artistry in an industry that was still young and fresh. Both Williams and Graham are visibly proud of their creation, despite scope cuts that removed several worlds from the shipped game. “I think the weirdness of the story that we all envisaged came across really rather wonderfully,” Williams says as Graham chuckles in the background. “I know Harry would kick me black and blue [for saying this]—very early on, we had a very large mixing bowl… and we poured as many conspiracy theories as we could find. And then we stirred with great vigor, and poured out what ended up to be a remarkably and sometimes spookily coherent story. So I was really proud of it at the end. I wasn’t proud of all of the bugs… but we were forced to get the game out.”

As one of the first games to use motion capture, there were naturally technological limitations like reduced frame rates that the team had to tackle for the game’s experimental cutscenes. It was especially challenging for Williams, who came from a film and TV background and recalls the framerate issue as an “enormous compromise” to work on the average PC at the time.

“We did [the motion capture] in North London… in a very very grotty old studio,” he says. “The data that came out of the motion capture was so messy, it took an inordinate amount of time to clean it up so that you could even possibly use it.”

One of the most intensive sequences was a medieval-themed cutscene—a shadowy affair filmed in black-and-white that adds a real textural cinematic depth that one wouldn’t expect of a game of its time. And to make things even more challenging, Williams recalls that QA and localization weren’t built-in parts of the development process back then, and that ultimately Drowned God was very much a ’90s game: everybody was still making it up as they went along.

A conspiracy for today

Today, the Drowned God rights are shared between Williams, Graham, and Harry Horse’s estate; any surviving material for the planned sequel, CULT, lies in the hands of the estate, which didn’t respond to my emails. “I still get the odd person who gets through to contact me who’s still quivering in their bunkers, wanting to know if there’s any plans for sequels, which is always quite gratifying,” Williams says with a laugh.

After all these years, besides providing Williams with a “marvelous number of after-dinner stories,” the behind-the-scenes tales of Drowned God are as inscrutable as the late Harry Horse, and probably are best left that way. “I think it probably cured me of continuing to develop games, and allowed me to do something slightly less exciting and exotic,” Williams says, reflecting on the six months he spent crunching while also caring for his young children.

Graham describes it as “a real education” even though he’s never even played the finished game. “This is blasphemous,” he says. “I was never interested in games, and I’m still a bit in that corner. But my impression, my feeling was one of genuine excitement because I hadn’t worked in this sort of medium before.”

When I ask Williams why he thinks Horse would have hated his “mixing bowl” description of the conspiracy narrative, Williams admits that he didn’t personally leap “feet-forward” into believing the truth behind the tales that drove the game’s plot; on the other hand, he finds it amusing that today we know that the US government has taken aliens seriously all along. “So whilst Pig Man isn’t walking around the streets of Los Angeles—though he may be—there are huge advances in genetics now, which means the dividing line is blurred,” says Williams. “The atmosphere is so febrile now that I think Drowned God’s time has come, but probably not in a point-and-click game.”

For Graham, Drowned God seems to be more of an exploration of the power and potential of belief. “I believe most of it, because I want to believe that sort of thing. I’m not serious, by the way,” he jokes. “But it’s infinitely mineable in that there’s so much that’s available, which is so dramatic and possible, it’s a delight juggling with it, really.”